Linklater's Nouvelle Vague: Weaving Cinematic History Through Godard's Lens

Linklater's 'Nouvelle Vague' masterfully recreates Godard's revolutionary 'Breathless' through authentic locations and mesmerizing performances, earning critical acclaim and Netflix success. This cinematic homage captures the explosive birth of French New Wave cinema with stunning black-and-white visuals and profound artistic integrity.

The cobblestone streets of Paris shimmered like scattered film reels under the autumn rain as Richard Linklater's camera captured a revolution in motion. Fresh from the triumph of Blue Moon, the visionary director plunged into 1959 France with Nouvelle Vague, a biopic dissecting the volcanic creation of Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless. This cinematic Russian nesting doll—a film about filmmaking that birthed the French New Wave—premiered at Cannes to thunderous applause before landing on Netflix in 2025, its 4:3 black-and-white frames serving as both homage and time machine. For Linklater, shooting entirely in French felt like navigating a labyrinth with borrowed senses, while newcomer Aubry Dullin stepped into Jean-Paul Belmondo's worn leather jacket with the trepidation of a tightrope walker crossing the Seine on a wire. The result? A shimmering tapestry holding 89% on Rotten Tomatoes and Netflix's second-largest foreign film acquisition after Emilia Pérez.

The Alchemy of Recreation

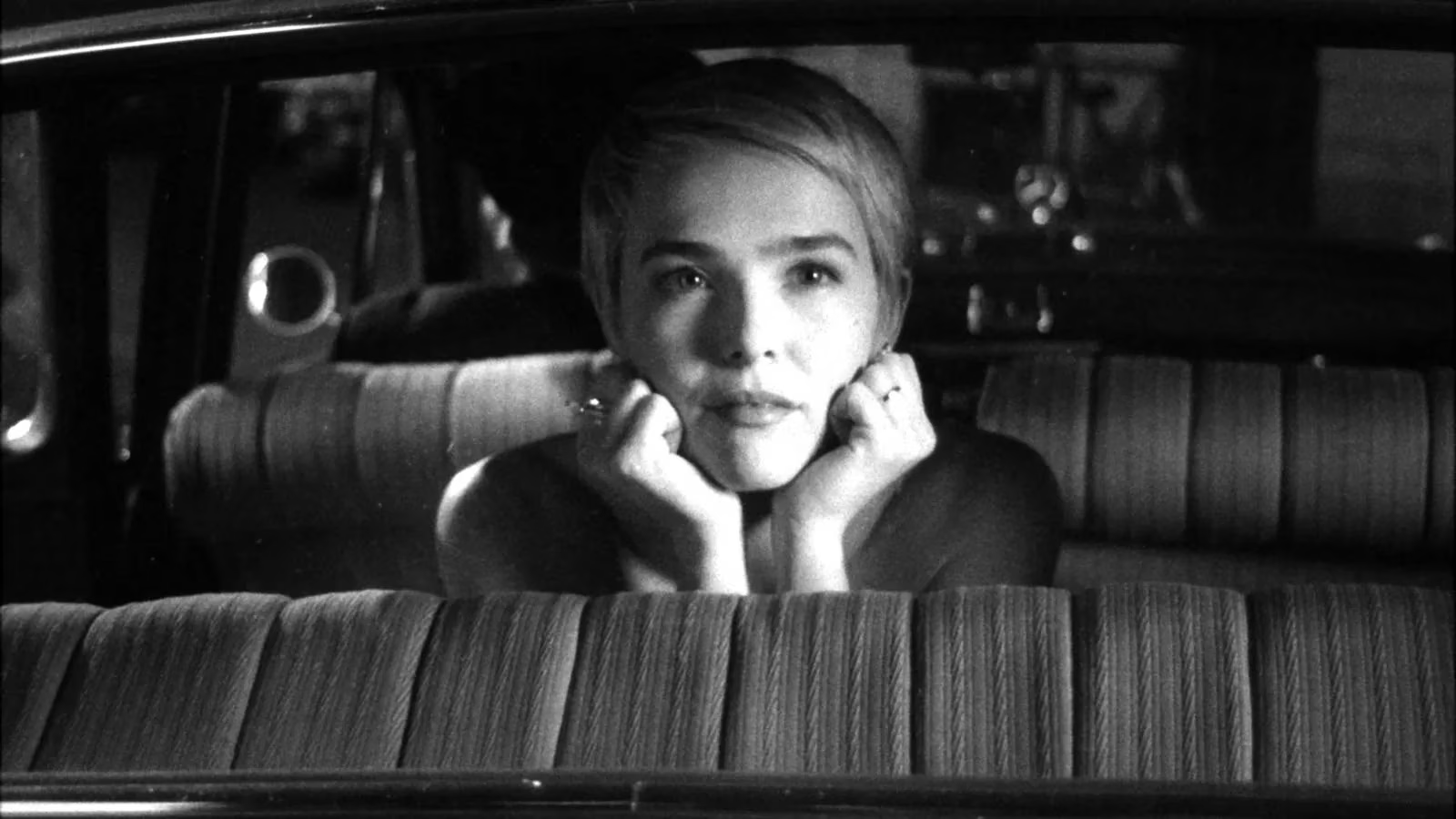

Linklater's approach to Nouvelle Vague was less traditional biopic and more archaeological excavation. By filming on the actual locations where Godard shot Breathless—including the fateful street where Michel Poiccard meets his end—the production became a spectral dance between past and present. Zoey Deutch, reuniting with Linklater after Everybody Wants Some!!, described the meta-experience as "living inside a hall of mirrors." During Belmondo's death scene recreation, Dullin recalled palpable ghosts: "We were shooting on the actual street... there's a picture of Belmondo playing Poiccard right there." The uncanny authenticity extended beyond sets; when Deutch returned months later for promotional photos, an elderly woman emerged from a nearby apartment, whispering, "I was here when you filmed the scene," a moment Deutch cherished like discovering a forgotten love letter in a library book.

Casting Lightning in a Bottle

-

Zoey Deutch as Jean Seberg: Facing the pressure of portraying an icon, Deught approached Seberg as a "kaleidoscope of fractured light"—simultaneously fragile and luminous. Her chemistry with Dullin became the film's pulsating heart, their off-screen camaraderie bleeding into nuanced interpretations of Seberg and Belmondo's relationship. "We embellished their mutual adoration," Deutch admitted, "like adding unexpected spices to a classic recipe."

-

Aubry Dullin's baptism by fire: The unknown actor’s transformation into Belmondo bordered on alchemy. So convincing was his embodiment that audiences constantly asked Deutch if he was Belmondo’s secret son—a notion Dullin met with bewildered humility. His sole mission? "I just wanted his family to see Belmondo on screen and say, ‘That’s him.’"

-

Guillaume Marbeck’s Godard: Tasked with playing the volcanic young director pre-fame, Marbeck focused on Godard’s creative terror—that knife-edge moment "when you have a vision that could excite people, but you’re unsure if anyone will follow." His performance captured Godard’s method of liberating actors through controlled chaos, particularly with Seberg.

Directing Dual Revolutions

Linklater found poetic symmetry in releasing Nouvelle Vague alongside Blue Moon. "They’re in conversation," he reflected. "One’s about an artist’s explosive beginning, the other about being left behind by time." Yet Godard, he noted, "always left the times before they left him—a shark never stopping its swim." The director’s fascination lay in Godard’s rebellious methodology: stripping away scripts to demand raw spontaneity from actors. Linklater compared it to "throwing a painter into a hurricane and demanding they capture the storm’s eye." This tension crystallizes in Marbeck’s scenes with Deutch, where Godard deliberately frustrates Seberg to unleash her authentic self—a gamble that birthed cinematic history.

Technical Sorcery and Legacy

Linklater’s formal constraints—French dialogue, monochrome palette, boxy 4:3 ratio—weren’t mere affectations but spiritual conduits. The aspect ratio alone functioned as a "visual sonnet" to 1960s celluloid poetry. Meanwhile, the film’s Cannes triumph and subsequent Netflix deal signaled a cultural moment. As Dullin filmed Belmondo’s final moments on that hallowed Parisian street, he felt history ripple: "We’re making it right here." For modern audiences, Nouvelle Vague offers more than nostalgia; it’s a living map to cinema’s rebellious heart, proving that revolutions begin with a single frame.

| Technical Highlights | Emotional Core |

|---|---|

| Shot entirely in French | Deutch & Dullin’s electric chemistry |

| Authentic 1959 locations | Marbeck’s portrayal of Godard’s creative anxiety |

| Black & white 4:3 cinematography | Linklater’s love letter to artistic risk |

In the end, Nouvelle Vague transcends biopic conventions to become a shimmering ouroboros—a film about ignition that itself ignites new wonder. As Godard once shattered rules, Linklater reassembles them into a mosaic that glows with timeless urgency.